At the beginning of the CAP system, Mark Wilmer Pumping Plant lifts water more than 800 vertical feet up Buckskin Mountain. But then what? How does all that water enter the CAP canal? It enters through a tunnel, specifically Buckskin Mountain Tunnel.

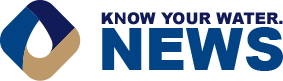

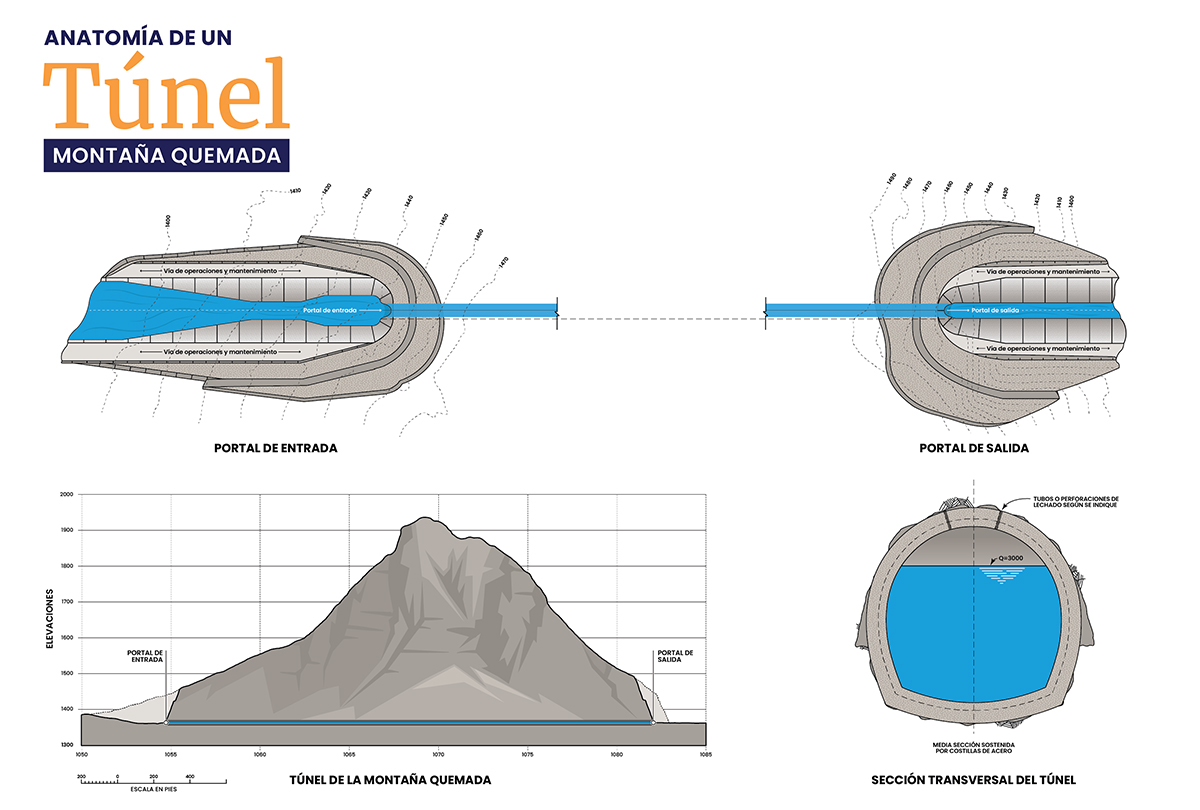

Buckskin Mountain Tunnel is the first of the four primary tunnels in the CAP system. It is nearly seven miles long and 22 feet in diameter, making it both the longest and largest tunnel. The other tunnels – Burnt Mountain, Agua Fria and Tucson – may be smaller and shorter, but have similar basic anatomy. Regardless of size, they’re all equally important, ensuring water can pass through mountainous terrain.

This infographic specifically looks at Burnt Mountain Tunnel, which is in Maricopa County, approximately 60 miles west of Phoenix. It is 19.5 feet in diameter and .6 miles in length. At the inlet, water is funneled into the horseshoe-shaped tunnel where it flows, by gravity, to the outlet. There, it transitions from the horseshoe shape back into the trapezoidal shape of the canal where water continues its journey, supplying water to the most populated regions of Arizona.

You may wonder why engineers decided to build a tunnel through the mountain instead of going around the mountain. The bottom line is cost. The shortest distance between two points is a straight line — even when it’s through a mountain — making it also the most economical.

Here’s the engineering behind it. The slope of the CAP canal is 0.00008 ft/ft which equates to 5 inches of drop in a mile. The Bureau of Reclamation optimized the alignment of the canal to maximize the distance the canal could follow the natural grade of the existing ground while steering clear of obstacles like mountains.

Going around a mountain would have cost more because of construction of additional miles of canal, construction of specialized canal sections to maintain the canal slope around the mountain (elevated embankments or excavation through rocky soils) that are more expensive, and increased property costs.

Like inverted siphons, tunnels are another critical — and often hidden – piece of CAP infrastructure, an engineering marvel that ensures reliable water deliveries to Maricopa, Pinal and Pima counties.

Al comienzo del sistema CAP, la planta de bombeo Mark Wilmer eleva el agua más de 800 pies verticales hasta la montaña Buckskin. Pero, ¿qué pasa después? ¿Cómo entra toda esa agua en el canal CAP? Entra a través de un túnel, específicamente el túnel Buckskin Mountain.

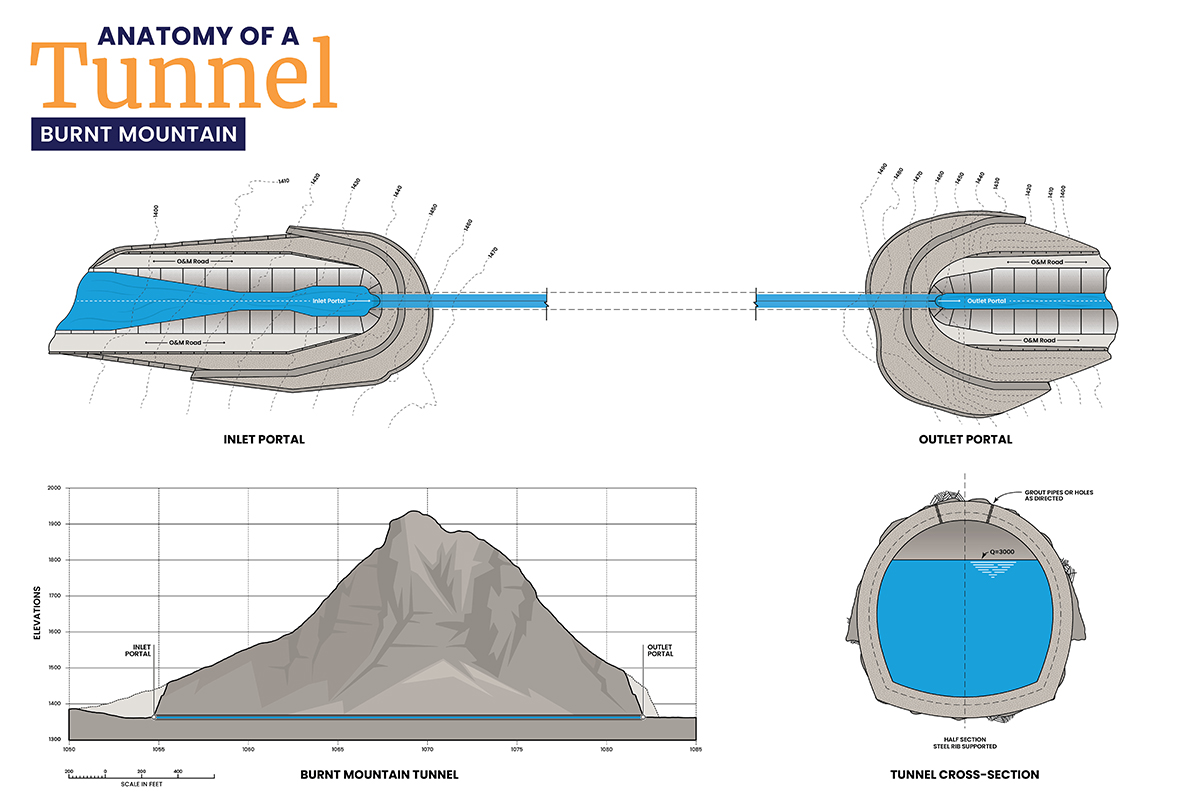

El túnel Buckskin Mountain es el primero de los cuatro túneles principales del sistema CAP. Tiene casi siete millas de largo y 22 pies de diámetro, lo que lo convierte en el túnel más largo y más grande. Los otros túneles (Burnt Mountain, Agua Fria y Tucson) pueden ser más pequeños y cortos, pero tienen una anatomía básica similar. Independientemente del tamaño, todos son igualmente importantes, ya que garantizan que el agua pueda pasar a través del terreno montañoso.

Esta infografía analiza específicamente el túnel Burnt Mountain, que se encuentra en el condado de Maricopa, aproximadamente a 60 millas al oeste de Phoenix. Tiene 19,5 pies de diámetro y 0,6 millas de longitud. En la entrada, el agua se canaliza hacia el túnel en forma de herradura donde fluye, por gravedad, hacia la salida. Allí, pasa de la forma de herradura a la forma trapezoidal del canal donde el agua continúa su recorrido, suministrando agua a las regiones más pobladas de Arizona.

Quizás se pregunte por qué los ingenieros decidieron construir un túnel a través de la montaña en lugar de rodearla. La cuestión es el costo. La distancia más corta entre dos puntos es una línea recta, incluso cuando se atraviesa una montaña, lo que la convierte en la más económica.

Esta es la ingeniería detrás de esto. La pendiente del canal CAP es de 0,00008 pies/pie, lo que equivale a 5 pulgadas de caída en una milla. La Oficina de Recuperación optimizó la alineación del canal para maximizar la distancia que el canal podría seguir la pendiente natural del terreno existente mientras evita obstáculos como las montañas.

Dar la vuelta a una montaña habría costado más debido a la construcción de millas adicionales de canal, la construcción de secciones de canal especializadas para mantener la pendiente del canal alrededor de la montaña (terraplenes elevados o excavación a través de suelos rocosos) que son más costosos, y el aumento de los costos de propiedad.

Al igual que los sifones invertidos, los túneles son otra pieza fundamental (y a menudo oculta) de la infraestructura del CAP, una maravilla de la ingeniería que garantiza un suministro confiable de agua a los condados de Maricopa, Pinal y Pima.

KRA: Project Reliability

Providing reliable and cost-effective operations, maintenance, and replacement of CAP infrastructure and technology assets